room door, interlocking wood joinery on the

staircase, ebony pegs covering all the nails and

screws.

I couldn’t help but wonder: If David and

Mary Gamble moved to Pasadena for the

sunshine, why was it soooo dark in here? Our

guide “enlightened” us: in 1908, electricity was

brand-new and people were accustomed to

soft candlelight, so even a 16-watt light bulb

seemed bright. (For authenticity, the house still

burns 16-watt bulbs.) People were also wary

about the effect of this newfangled electricity

on the human body. They wanted it deflected

from them, which explains why the Gamble

House’s chandeliers direct light up to the

ceilings, not down into the rooms.

Times were indeed different back then, as

we discovered on checking out the front hall

closet. Inside, a secret door led to the servants’

area. Domestic staff would dash through

to greet guests at the front door and then

literally fade into the woodwork. The Gambles

themselves didn’t want to see or hear the help;

they never set foot in the kitchen, even to grab

a sandwich.

Family members lived here until the 1960s,

when they considered selling the house – at

least until a potential buyer observed how dark

it was inside and his wife was overheard to say:

“Don’t worry, dear. We’ll just paint it white!”

Realizing that they had to preserve Greene

and Greene’s jewel-box legacy, the family handed the house over to the city and the USC School of Architecture, which

have handled it with care. (Workers restoring the outside rafter tails actually scraped out dry rot with dental tools.) The

expansive lawns and warm breezes around the house helped me feel the atmosphere that attracted people to Pasadena

in the first place.

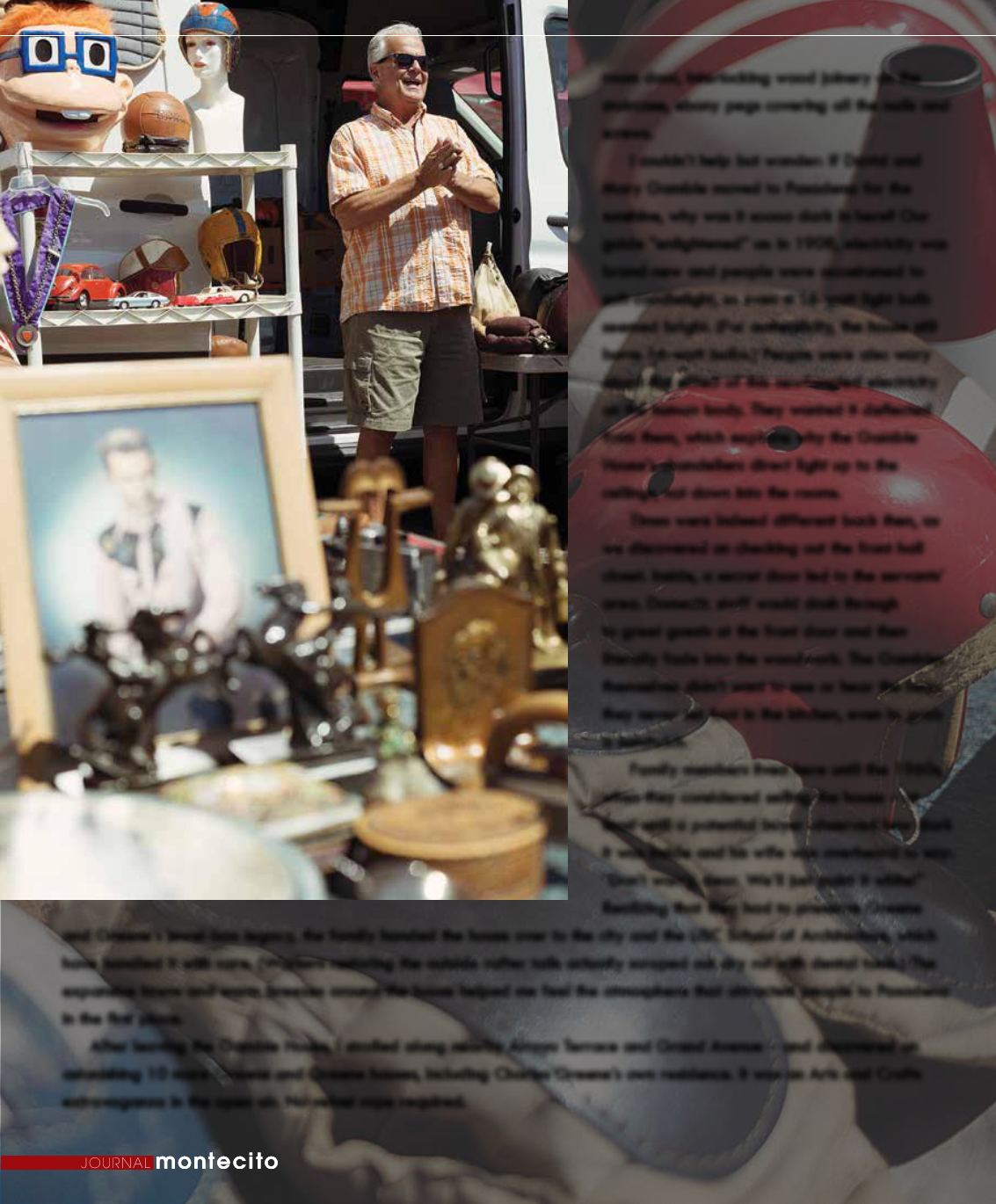

After leaving the Gamble House, I strolled along nearby Arroyo Terrace and Grand Avenue – and discovered an

astonishing 10 more Greene and Greene houses, including Charles Greene’s own residence. It was an Arts and Crafts

extravaganza in the open air. No velvet rope required.

summer

|

fall

47