Basic HTML Version

84

summer

|

fal l

club. Dr. Elmer J. Boeseke, son of a pioneer Santa Barbara hardware family,

recalled that he attended a dinner hosted by Robert Cameron Rogers, poet

and editor of the

Morning Press

, at which it was suggested over a glass of

champagne that Boeseke, being quite a horseman, ought to dedicate his life

to polo. If he agreed, he was promised a pony named Merry Legs.

Boeseke recalled, “After strenuous efforts of backhands, forehands,

and missing the ball mainly, I became sufficiently proficient to be placed

among the players.” (Indeed, the Boeseke family was destined to become

a driving force for polo in Santa Barbara, with Dr. Boeseke breeding and

training many of the ponies.)

With the advent of wet weather, the team gave up the Agricultural

Park at the Estero and moved to the foot of the Mesa at the west end of

Carrillo Street where they had leased 22 acres of higher and drier ground.

Boeseke recalls that notable among the early members of the Polo

Club were Clinton B. Hale, their first president who was also president

of the Santa Barbara Club, and Robert Cameron Rogers, “who during

intervals between chuckkers… would go to the end of the line and walk

his horse up and down communing with his own thoughts. To this day no

one knows what they were.” (Poetic ones, no doubt.)

Joel R. Fithian, rancher and owner of the Santa Barbara Country

Club, used to drive his stage coach to the Westside field, and Jack Colby

on his mare, Colleen, would come charging down the field as bystanders

fled far and wide since it was impossible to stop her.

At a polo match between Riverside and Santa Barbara in 1901,

Sidney Stillwell, Francis Underhill’s horse trainer, acted as Umpire.

Deputy county clerk Ernest Wickenden, Charles Fernald (son of pioneer

Judge Fernald), “Bob” Rogers, and Charles Ealand, who worked for his

father’s State Street Market at the time, took to the field for Santa Barbara.

Though the game was hotly contested, the

Morning Press

reported, “The

superior team work of the Riverside men became quickly evident and

eventually won them the game.”

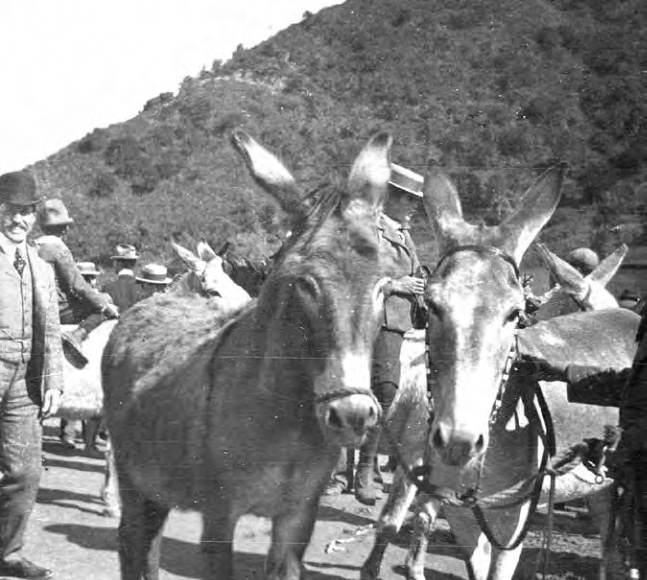

The three-day event ended with a gymkhana that included a long

distance drive with a polo ball, a 50-yard dash around stakes, and a

comical burro-back polo game between Riverside and Santa Barbara.

Polo had caught Santa Barbarans’ imagination, and by 1902 the Polo

Club had 40 members. Horseless polo enthusiasts found ways to play using

bicycles, rollerskates and automobiles. One young lad and his friends were

inspired to take their families’ work horses to Summerland where on a level

field they formed two teams, and with mallets fashioned from discarded

fishing poles or slender fence posts filched from an unguarded field, they

proceeded to attempt a game of which they had only heard.

Soon reports came to the Sheriff’s Department of some Santa

Barbara youths who were running amuck, “misusing” their horses near

Summerland on Sundays. Apparently, in the fervor of the game, some of

the boys were using their makeshift mallets to urge their horses to greater

efforts and were not above turning them on each other as well. The local

constabulary saw to it that the horses were safely padlocked on Sundays

and the Junior Polo Club was disbanded.

(left) Polo Burros pose for the camera just before a rousing gymkhana chukker between Riverside and Santa Barbara (Courtesy Montecito Association History Archive)

(right) After Riverside trounced the Santa Barbara team in the April 1901 polo match at the Westside field, the two teams tried their luck on burros

(Courtesy Montecito Association History Archive)